By Petra Nyendick

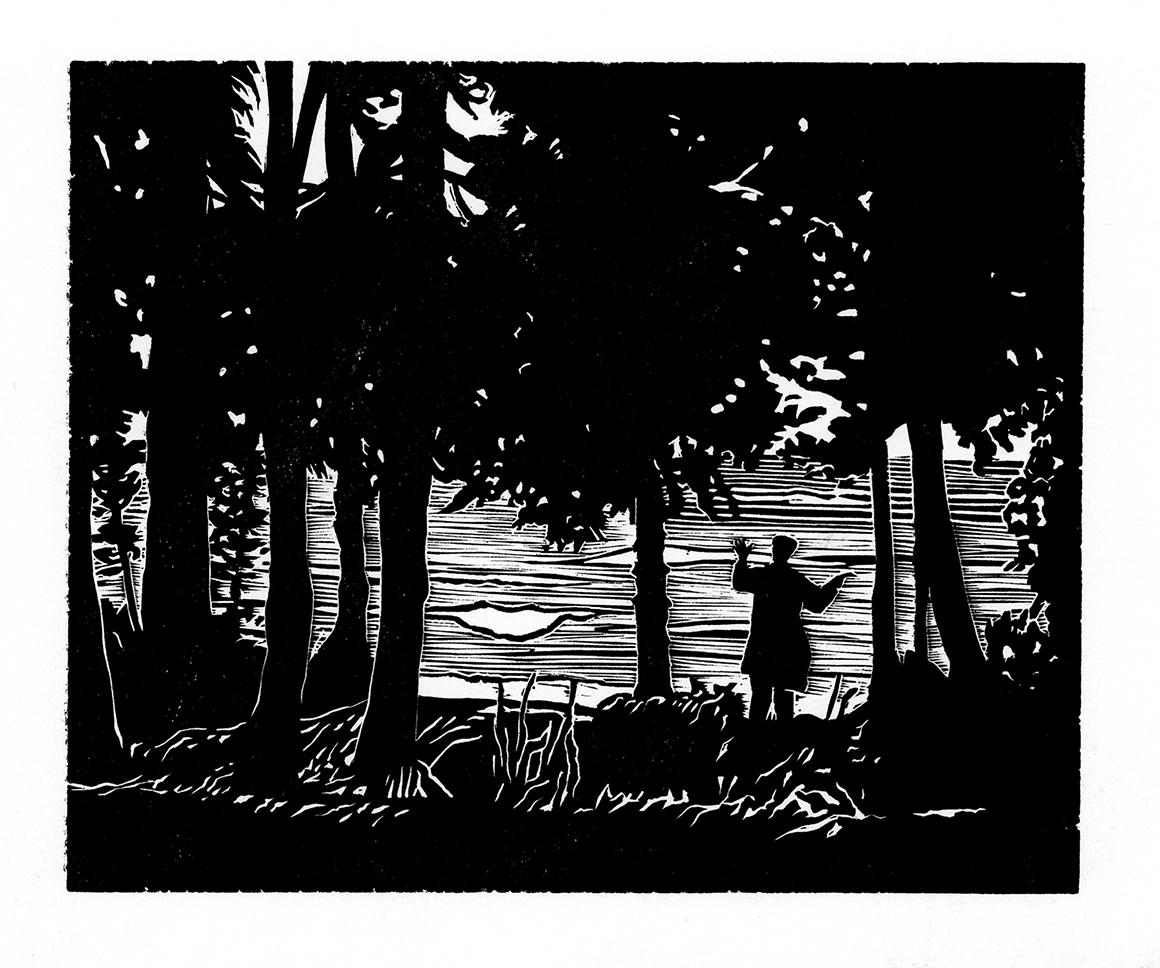

Silence invites you to an art exhibition and sale of a series of 20 selected linocut images from Architecture of Music by Toronto artist Stefan Berg. The artist will be in attendance at the opening on June 3rd, 7-9 pm, to discuss his work. Please join us for a stimulating evening of image and sound. Wine, beer, coffee and kombucha will be served.

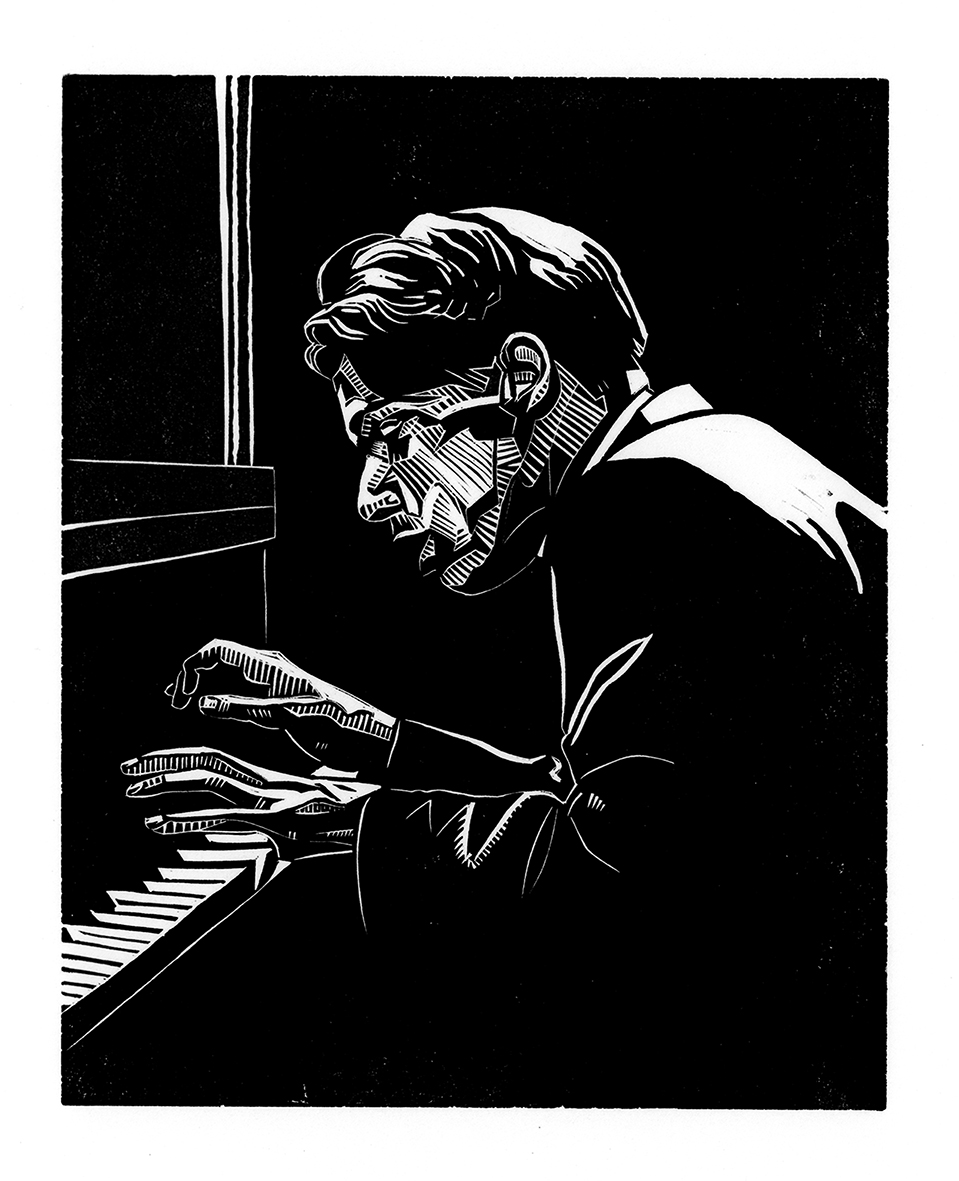

Stefan Berg works in the form of the wordless novel using lino-block prints to create sequential single-image narratives. His work has been exhibited in Canada and the United States, and has received positive reviews from The Toronto Star and The Globe and Mail. Architecture of Music is Berg’s second wordless novel, a series of 50 images in response to Glenn Gould and the notion of solitude. His previous work Buddy Bolden’s Last Parade, published in 2008 by the Porcupine’s Quill is a a series of 70 images depicting the culture of New Orleans parade music and the legend of Buddy Bolden.

The following interview with Stefan by Silence board member Martha Nandorfy opens the discussion about the artwork.

How does the oxymoron ‘wordless novel’ describe this exhibit? Do you use the genre ‘novel’ to mean that you are creating a narrative? Even if a picture is worth a thousand words, how much is left to the viewer’s imagination?

This exhibition is a selection of images from a larger series of 50 linocut images, to be published in book form as a sequence of single images without words. Pictorial narrative has a long history and includes visual sequences in a variety of media, from the wall decorations in Egyptian tombs, and illuminations to silent films, and comic strips. The term ‘wordless novel’ first appears in the 1920s with the work of Frans Masereel, followed by Lynd Ward in the 30s, and Laurence Hyde in the 50s, each artist telling their story through a series of wood engravings.

The turning of the page is what is most significant about the wordless novel: the power to control a succession of images in time. In this way it is akin to the silent film. Wordless novels are filled with language; it is in the reader’s hands to develop their own interpretation, and that goes for an exhibition of images on a gallery wall as well

Using Glenn Gould, Canadian iconic pianist, the Gould we know and all his tropes, I take advantage of and then subvert readers’ pre-existing sense of him, reinterpreting the idea of Gould. The unconventional narrative and free association comes from Gould himself speaking of his own views on creativity.

If synesthesia is the basis for your exhibition’s title: ‘Architecture of Music,’ does it also suggest something about your own process, and how viewers might relate viewing images to imagining music and storytelling?

My exploration of medium and technique is analogous to Gould’s process and use of technology… “the architecture of the music” is a line I have taken from Gould in interview. For me the process of flipping the page, or reading the images as still frames from a film, brings the images to life; they become musical together. The contrast of black and white, positive and negative space, line and texture, size, shape, orientation and sequence are each considered in relation to tempo, speed, both audible and visual noise, and most importantly the silence of sound (Gould is best known for his perfectly timed empty spaces).

How did you become interested in Glenn Gould and from where did you draw the inspiration for these images?

I grew up listening to Gould. I grew up around the corner from where he grew up in Toronto. I often think of his music when walking in our neighbourhood. This project is an interpretation of Gould personal to my own lived experience.* I worked on this story over two separate occasions at my family cottage in Bruce County. I was interested in working within the same creative circumstances Gould constructed for himself. Rather than making a statement, or documenting his life, my project functions as a visual and poetic metaphor for his creative process. I predominately work from observation and the majority of these images were drawn first hand. The images which depict Gould were created through a process of collage, referencing multiple sources: my own photography, the photography of others, and perhaps most importantly film footage.

*Within the wordless novel genre there is a common theme: the artist leaves the city to find meaning in the world and wilderness (Wild Pilgrimage by Lynd Ward, Passionate Journey by Frans Masereel.) I find it interesting that Gould’s favourite book was The Three Cornered World.

Can you speak about why you depict Glenn Gould in different environments, such as the scenes of nature versus cityscapes or buildings?

Gould was greatly influenced by his own imagination of the North. At the age of 35, shortly after retiring from performing, Gould began working with the CBC to produce The Idea of North, a conceptual radio documentary contemplating notions of solitude and the identity of place. I believe the North remains a strong source to be tapped for creative inspiration, and the coming together of such a mysterious space with one of the great dynamic minds of our age has always intrigued me. My project draws upon this very interaction.

What does his music recall visually? This was task. The architecture of music consists of a visual vocabulary, from repetition of form, juxtaposition of mathematical structure, to the harmonic and analog form. The different environments or sequences create a rhythm, tempo, pace, the passage through space in relation to time, and the presentation of movement.

On the other hand, from a plot-driven examination, my project does depict some key moments in Gould’s life. The recording of Gould’s debut album, Goldberg Variations (1955), the creation period of one of Gould’s only compositions, Strings Op.1 (1956-60), and Gould’s last public performance (1964), juxtaposing Gould’s relationship to the recording studio, the seclusion of his cabin, and the stage–essentially urban and rural environments.

Are there any specific pieces of music we should be listening to, or might imagine while viewing the exhibit?

Gould’s extraordinary career was bracketed by two interpretations of J. S. Bach’s Goldberg Variations. It was his first recording of the work in 1955 that established his international acclaim and the second version of 1981 proved to be his last recording. The first is technically demanding and energetic. In contrast, the second abandons this showmanship and replaces it with a more introspective interpretation. The 1955 recording was considered idiosyncratic, the 1981 recording a symbolic testament to Gould’s immense talent for reinterpretation.

My project literally interprets the difference between the two Goldberg Variations, however these are my favourite pieces of music by Gould, which I listened to while working:

-Bach: Italian Concerto, BWV 971 – 3. Allegro Vivace

-III Precipitato – Piano Sonata N. 7 Op. 83

-Allegretto from Sonata No. 17 in D minor, Op.31 No.2

-Bach: Goldberg Variations, BWV 988 – Variatio 5 A 1 Ovvero 2 Clav.

-Bach (JS): Two Part Invention #13 In A Minor, BWV 784

Can you explain what exactly you mean when you say that your project literally interprets the difference between the two Goldberg Variations?

The structure of my narrative is in five parts: Aria, Audience (final performance 1964), Strings Op.1 (efforts to compose his original composition 1956-60), Goldberg Variations (relationship to the studio 1955), and The Idea of North (1967). The narrative begins with busy, energetic compositions, with a high degree of texture, contrast, black line on white ground –and ends with a softer, restrained, more subdued quality, a greater degree of white line on black ground. This reflects the difference between the energetic Goldberg Variations of 1955, with which he began his career, and the introspective Goldberg Variations of 1981, with which he ended. The last images in my narrative follow a sequence of landscapes of North Ontario, and are predominately solid black images of Gould playing the piano. This final sequence is conceptually linked to Gould’s documentary The Idea of North. I propose that Gould was an explorer; he gave up Europe and the United States for the isolation of the Canadian winter (the Canadian landscape being an exotic environment from the viewpoint of the ‘old world’), and that “the idea of north” suggests finding inner peace and artistic liberation through self reflection. For Gould to “go north” means to go into yourself.

What do you particularly enjoy about working with lino-block prints? Is there something about the history of this medium or how contemporary youth read the world that inspired you to tell this story in linocut images?

The traditional practice of engraving is the foundation of my project. Relief printmaking is certainly experiencing a renewal, and due to a cultural shift towards images, there is greater interest in the wordless novel. I have been experimenting with a process of superimposing multiple linocut images. Throughout this project I have ghost printed images in a soft grey tone, then overlaid the prominent image in black.

I am interested in Gould’s own layering of audio recordings, and contrapuntal technique in which independent melody lines play simultaneously. Gould was not only the subject of my project, he provided the conceptual and structural framework for pushing the boundaries of my genre; for Gould, reinterpreting classical scores, for me, repurposing traditional printmaking.

The exhibition is free and physically accessible to the public. Silence is located at 46 Essex Street in Guelph, west of the Farmer’s Market, one street south of Waterloo. Street parking is available. For more information, please visit www.silencesounds.ca or email [email protected].