By Katie Wilde

all Photos by Elizabeth Bell unless otherwise marked

“‘Why are you rubbing the drums?’ you may be wondering. Well, otherwise, they go thud.”

This was the short, lighthearted version offered to the Guelph Youth Singers by Jan Sherman of Wiiji Numgumook Kwe, the Guelph Women’s Drum Circle, as they navigated their first joint rehearsal. In all seriousness, she also explained that the drums are “grandmothers”, representing the spirit of their ancestors. They are each handmade from real hide, and the warmth from the drummer’s hand rubbing the surface helps the sound ring out. It is also a “way of connecting your energy” in preparation for the song to come.

From the beginning, the collaboration between the Guelph Youth Singers Choir III and SATB Choir emphasised active participation for the youth in aboriginal traditions, while respecting the sacred. For instance, one of the young singers presented tobacco wrapped in red fabric to Wiiji Numgumook Kwe in order to officially welcome them into the Guelph Youth Music Centre rehearsal space. The Drum Circle then introduced themselves, and sang a welcome song.

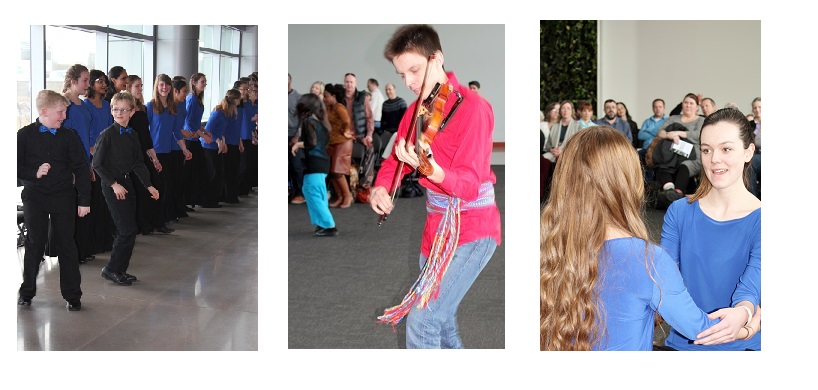

Photo by Ken Gee.

Photo by Ken Gee.

This rehearsal was in preparation for Honour Song, a unique concert held this past Sunday at the Linamar building in Guelph’s industrial north end. This may seem like an odd venue choice, but the spacious atrium of The Frank Hasenfratz Centre of Excellence proved both unusual and striking. A gigantic open space that otherwise may seem more akin to a car showroom, it includes two living walls, an enormous bank of windows, and is open and full of light. As Markus Howard, GYS’s choir director said, “It was as close as we could come to being outside in February.”

Markus Howard is the new (since 2013) director of the youth choir, and together with Jan Sherman of Wiiji Numgumook Kwe, they envisioned a cross- cultural celebration in which Choristers, audience and drummers would celebrate authentic First Nations, Me’tis, and Inuit culture including drumming, poetry, singing and storytelling and introduce our community to previously unexplored sound, rhythm and repertoire. Honour Song was a prime example of this. While it’s not reasonable to expect to understand indigenous culture after one concert, all present were offered a rich and memorable experience full of exposure to First Nations traditions. At the same time, the Western-style choral arrangements of the GYS offered both contrast and interest through borrowed and blended Native elements. Together they illustrated the universal power of song, rhythm, and story that threads through all human cultures.

Guelph Youth Singers (GYS) is a national award-winning professional choir, and all the hard work they put in through regular training and performance shows clearly in their refined sound, impressive control and wide range of expression. By some contrast, the Guelph Women’s Drum Circle are not professionally trained, and do not consider themselves performers. To think this would prevent them from sounding incredible would be a mistake. Singing and drumming is an integral part of their spiritual practice, and it’s perhaps from this that the power of their emotive expression, compelling storytelling and infectious sense of celebration derives.

Wiiji Numgumook Kwe roughly translates into English as “We Sing Together in Unity.” Culturally, this has significant meaning. The drum circle is made up of women from all cultural groups in order to honour the Medicine Wheel Teachings. In their words, “We share songs as part of our spiritual practice, raising our voices with the heartbeat of Mother Earth with the intention of sending joy, and healing into the world.

The Medicine Wheel was front and centre in the Honour Song concert, quite literally. A cloth representation was placed on the floor in the centre of a space ringed by a C-shaped audience. Some attendees filing into the space remarked to each other “Oh, it’s in the round,” a term that describes this type of audience/artist arrangement in performance, and is often associated with intimate, immersive or interactive experiences. Honour Song was certainly all of those things. The Medicine Wheel also inspired the format for the concert as a whole. The circle divided into four colours: red, white, yellow and black, is a deceptively simple icon imbued with many layers of meaning. The colours represent various races and peoples, including First Nations, Asian, European, and African. They also represent compass points, and each direction has its own set of associations, from birth to death, through love, reflection, respect, celebration, spirit of the natural elements and much more.

The afternoon concert began with a territorial acknowledgement. It was likely the first time many of the concert-goers had heard of the Attawandaronpeople, who lived on the land we now call Guelph. They were known as “The Neutral People” for refusing to take sides in the conflict between English and French settlers, and for welcoming all peoples into their territory to hunt and fish. The introduction continued with a traditional Mi’kmaq Welcome Song, Quando Deh, shared by Wiiji Numgumook Kwe.

The programme was shaped into a journey around the Medicine Wheel, and so began with the theme of East/Fire/Spirit. The title Honour Song comes from the eastern Mi’kmaq Honour Song. Arranged by Canadian composer Lydia Adams and performed by GYS Choir III, it begins on one haunting note, and shifts slowly into controlled dissonance. There are singers in the centre area, ringed by audience members. There are singers behind the audience and in the aisles. A loon calls out. Something whistles behind us, clicks over here, chirps over there. The chorus continues to grow their odd chord as a wolf howls and the wind joins him. All these sounds are created by the young people, and they are all achingly beautiful. The song grows and swells, and when the drummers join it’s almost hard to believe we’re hearing it live, it sounds so perfectly beautiful.

As the concert programme moves around the Medicine Wheel, the songs are introduced with their history, or the story that accompanies the song. The story is an important part of First Nations song tradition. Lois Macdonald, one of the women from the drum circle, explained the concept of “gifting” a song. The sharing and learning of new songs is not done willy-nilly in aboriginal culture. Rather, a new song must be ‘gifted’, along with the story and restrictions that accompany it, and only then will it be taught by listening and repeating until it’s memorized. Story and song intertwined to palpable effect in Wishita (Water Song), in which a waterfall starts slowly as a spring from beneath the earth, grows into a brook, gaining volume and power to become a waterfall, then suddenly slowing at the bottom of the waterfall, and finally reaching ocean where it becomes one with those waters.

The loose translation of Wiiji Numgumook Kwe, “We Sing Together in Unity,” also describes one of the artistic hallmarks of Guelph Women’s Drum Circle and the traditional songs and prayers they sing. Unison is a type of vocal harmony, or non-harmony, where singers sing one melody in the exact same rhythm, timing and pitch. The SATB (Soprano, Alto, Tenor, Bass) Choir’s name is also revealing of their style of music: four part harmony, where different performers sing different notes simultaneously to create chords. The music chosen for the concert presented quite a challenge to the Guelph Youth Singers. According to their director Markus Howard, “Our rehearsal muscle had to change and adapt to this type of music. For example, we couldn’t use lyrics to memorize notes in the same way.” He went on to describe how vocables take the place of lyrics in many cases, and function as meditative singing. Much of what you hear sung in indigenous song is not actually any language, but “inter-tribal” vocables, whose sounds have no direct meaning but are able to convey emotion, and thus communicate across language barriers. The mix of First Nations languages, English, vocables, and other vocalisations such as animal and nature sounds was a highlight of this concert.

The involvement of the audience also made this a standout experience. Sometimes, there’s no quicker way to strike fear into the heart of a crowd than uttering the words “audience participation.” The ‘in-the-round’ seating format helped set the stage, literally and figuratively, for a more open response. Already there is a greater sense of equality and inclusion when the singers are on the same level and all around you. So when the Mé’tis mother and son (Kim and Rajan Anderson) from Manitoba came on to teach us a jig, everybody stood up and gave it a shot. If there was a meter for the sense of shared experience and laughter in the room, the needle absolutely shot upwards at that point. For a choral conductor, spontaneous audience sing-a-long is not part of the plan. Towards the end of the concert, there was more laughter when Markus Howard confessed that he had “never done this before,” but that the audience was invited to join in on the line “She won’t come back. She won’t come back again.” It seemed as though more audience members sang than after similar invitations, no doubt due to the conscious effort of the concert to foster togetherness, and the commitment of both GYS and Wiiji Numgumook Kwe to community.

As Jan Sherman said to the audience when we were invited to join on a line of one of their songs, “As soon as you use your sacred breath, you are a part of the circle. It takes the whole circle to move forward in the world. When you decide a group of people isn’t important, you break the circle.” On the final piece, Travelling Song, everyone in the room stood to face the four directions, one after the other. If we weren’t already standing when the song finished, it would have been a standing ovation.

I call encore for more of these types of opportunities to learn and honour our history, our peoples, and our planet through collective artistic and cultural experience.

Bravo and Miigwetch.